The New Battle for Bangladesh

Bangladesh’s post-Hasina politics is marked by a fierce contest between old elites and rising aspirants vying to fill newly opened power spaces. This debate is simply one front in this broader elite struggle reshaping the country’s political future.

Ever since that fateful afternoon on August 5, 2024, a meta debate has been dominating Bangladesh politics regarding the nature of the July events and the fall of the autocrat.

The debate is on whether to call the events a mass uprising or a revolution. We know that this debate is important because different political sides want to gain great political capital and power from the labelling of the July-August events.

There are also very individual dimensions to this debate and related politics. One way to understand the debate is to see it as a barely disguised battle for the elite space of the country.

The thesis of this article is that the uprising vs revolution debate is one expression of a broad and powerful struggle for supremacy between entrenched elites of the country and aspiring elites.

While the first group wants continuity for roughly maintaining the existing elite hierarchy, the other group wants to replace the hierarchy with a new one, with the aspirants on the top.

No side really wants radical change in social and economic structure; they just want themselves to be on top. And this landscape for elite struggle for dominance has been greatly impacted by new media and prevailing global political winds.

This is very common in history of elite politics, revolutions rarely change society and economy, they mostly replace one group of elites with others: elite turnover. There is a wave of elite turnover in politics happening all over the world; can Bangladesh be sequestered from the spirit of the times?

We still aren’t appreciating the implication of the ongoing elite turnover in the country since August 2024. This is the largest elite replacement in the country’s history since 1972 when defeat and departure of Pakistanis left the bulk of the elite spaces empty in politics, economy, bureaucracy, academia, media, culture, everywhere.

Maybe not to the same extent, but defeat and departure of Awami League from Bangladesh in August 2024 also created massive vacuums in elite space of the country.

However, unlike the monopoly enjoyed by Awami League and its supporters in 1972, there is no unopposed field now and a bitter struggle for occupying-maintaining elite space is taking place. If you look at events that have been transpiring since that August through a lens of elite analysis, you will see that little makes sense without that perspective.

During the first year of the Interim Government the elite struggle for dominance mainly was confined to palace intrigues. With the election coming up in a couple of months it is now increasingly open.

In this regard please also read Syed Akhtar Mahmood’s excellent article in Counterpoint titled “Forget the Elite. We Need To Think About Aspiring Elites.” He is mainly discussing elite turnover in the economy; we need to talk about political elites too.

Elite Theory of Politics

Elites are individuals in society who, by virtue of their positions in organizations and networks and because of the resources they command, can influence political outcomes of the whole society.

They are powerful enough that they cannot be suppressed without causing some political disruption. Not just politicians but business leaders, senior bureaucrats, military, community leaders, organization leaders, cultural figures also part of the elite.

The main contentions of the elite theory of politics are that the distribution, structure and behavior of elites in different societies in different times varies significantly and this variation in elite behavior can also significantly account for types of political regimes and political trajectories of countries and societies.

Even in democracies the real power resides among elites, change through elections just changes which faction of elites come on top and take control of the power of state. So, a comprehensive analysis of a political regime must include study of the elites.

Study of elite behavior is especially important for nations in transition like Bangladesh now because the power structure is unsettled. In Authoritarian regimes, like Hasina 2014-2024, power is concentrated in a smaller elite, but the structure is evident.

In democracies, ideally, power is institutionalized and open to all aspirants. In societies undergoing transition, divisions within the political elite undermine the hierarchical structures that organize power. Consequently, different groups vie for dominant positions within the political system.

In such circumstances, personal goals and ambitions tend to play an especially significant role. This is why it pays to study elites and powerful people individually during periods of transition.

Elite theory of politics was proposed in the modern era by famous Italian social scientists Vilfredo Pareto (of Pareto Rule fame) and Gaetano Mosca in the 1920s and 30s.

Ever since then, elite theory had to contend with conventional structural theories (economy, social and ethnic composition) or institutional theories of politics and political change. Elite theory has been subsumed into other mainstream theories, but it remains an important lens to analyze regime changes.

For example, economic and social changes are evidently important causes behind weakening and eventual fall of Sheikh Hasina regime, but elite defection from the regime during the July Uprising surely is one of the proximate causes of the spectacular downfall.

Technology and Elite Turnover

Elites are powerful in politics and society, but the composition of elites is not static. Generally, there is always a circulation of elites in society as old elites decay or die, and new aspirants take up positions in the ranks of the elite.

Revolutionary changes are, however, more sweeping, revolutions change entire classes of elites and replace them with a new elite class. At different times of history, rapid change in technology and economy also causes faster elite turnover.

Industrial Revolution and global trade created many new merchants and industrialists who took up places of landowning old elites. IT revolution is enabling rise of new elites in economy and politics.

There is also very powerful role played in history by media technology in disrupting and undermining old elite hierarchy. Pamphlets from the first printing presses in Europe broke apart the one Holy Roman Catholic Church and gave rise to Protestantism and hundreds of other Christian churches.

Newspapers and wider literacy generated the age of revolutions in 18th and 19th century. Radio technology was instrumental in spreading Fascist and right-wing ideologies and parties in early 20th century. And we now are in social media era. Politics is downstream to new mass communication technology.

A great elite disruption in politics, media, society and economy is happening all across the world because of social media. The recent Trump and Mamdani meeting in the White House has been described as a clear example of how new media has disrupted political elite in the US both from the right and the left.

Bangladesh’s media and cultural elites were already greatly disrupted by social media, but Hasina’s long autocratic reign kept the political hierarchy from getting turned over. Her fall has opened the field of political power not just among the remaining elites but for challengers from below.

Our Current Elite Conflict

Since by definition the number of elites, people who matter, in a society is not high, it is possible to study them individually and collectively. To collectively study the elites, social network analysis, survey, statistical analysis, computer simulation and many other empirical methods can be used along with more theoretical tools.

If we get to know candidates for the coming election from all the major parties, that will provide a treasure trove of data for political elite analysis. However, I don’t have access to any study of post-Monsoon Revolution political elites of Bangladesh. In its absence, indulge me with a few personal observations.

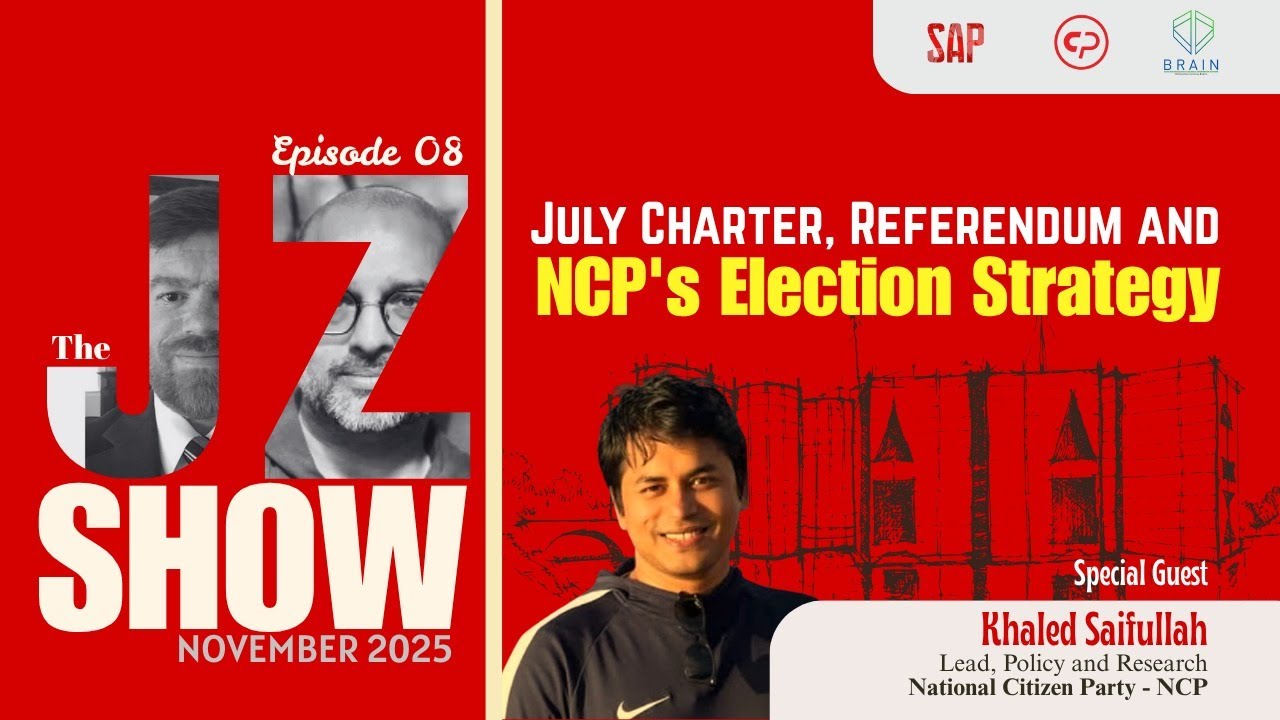

We can roughly divide current politically powerful actors into four camps. BNP-aligned elites comprise a large group that is just waiting to be officially the dominant elite. There is another group of actors orbiting the dual core of Interim Government and NCP.

It’s no secret now that this group has been trying their best to prolong the tenure of the interim government because current government is their main, if not the only, way to stay at the top of elite game.

Jamaat is rapidly marshalling and consolidating its political actors after many years of operating in shadows. And then there are loose groupings of other powerful actors like various Islamic groups, religious preachers etc.

Public face and behavior of the post-Hasina political elites clearly show that there is a class division among them. BNP-aligned actors generally belong to an entrenched political elite class.

NCP is comprised of new and young political actors, but they are backed by a few traditional political elites within and outside government. Jamaat’s case is interesting. It had entrenched elites in its leadership, but they were decimated by Hasina and old age.

After many years of political repression, there are very few elites in its political leadership although it has managed to attract many new members from professionals of all occupations. But these members are not in leadership ranks.

So, at this period in time, BNP could be safely termed as representatives of entrenched elites while Jamaat and NCP are mostly elite aspirants.

The class division among our present political actors has been amply demonstrated every day. BNP leaders have derogatorily spoken about NCP, Jamaat and young aspirants have embraced those classist attacks and weaponized them in counter.

One of the important tenets of elite theory is that social class plays a significant role in the development of a person’s interests and identity. Entrenched elites try to protect their positions with relations, networks and hereditary bequest but unless well organized under a common interest, they become complacent and more vulnerable to ambitious aspirants.

There is often a refrain among political commentators nowadays, even among Jamaat-sympathetic ones, that Jamaat is not ready for national power.

The party may have massively increased its popular support among all classes and all regions; it still does not have capable and experienced leaders who are capable of running a country of 200 million in the present world.

However, human ambitions are seldom commensurate with their abilities. In general, Bangladeshis are very confident and optimistic about their own ability to run the country.

Complacent Elites and Ambitious Aspirants

Another curious pattern in political discourse of the last few months is that while Jamaat and NCP leaders have been vigorously and consistently attacking BNP, BNP’s leadership can’t seem to muster enough will to hit back in kind. There may be more benevolent motives behind this restraint.

One gets the distinct impression that BNP leadership, veterans of decades of political battles with Awami League, 1/11 government, Ershad regime, is not yet in the frame of mind where they can regard Jamaat as its main political rival.

BNP leadership’s complacency toward the aspiring groups betrays another important part of elite conflict history. A country’s elites are often so engrossed or stuck in horizontal conflict mode with other elites that they overlook vertical threats from below.

The old guards seldom can fathom how ambitious or capable the aspiring elites can be.

There are also times when the old guard of elites are just too tired and decayed. Apart from Hasina’s long oppression, Bangladeshi elite ranks of all spheres have been severely decimated in the last couple of decades by elite exodus to the wider world.

Not only are the ranks thinned but many of the remaining already have one foot in the outside world or a safe exit prepared. The aspirants in general have more stake in the homeland and they have tenacity for a long game.

What about the role of political ideologies, political vision of the actors and groups in this elite struggle? Elite theory proposes that ideologies are mere tools for elites to mobilize support and organize displays of power.

That is why we should less look at ideologies of political actors and look more into their groups, networks, and their actions. A lot of politics behind wild demands of reform, fiery and contradictory rhetorics, encouragement of Mobocracy are aimed towards unsettling the entrenched elites.

The more the incumbent elites are unsettled the less they can organize a unified response to the challenge of aspiring elites. ‘Pseudo-revolutionary’ rhetorics and actions certainly originate in large part from that destabilization efforts.

What Now?

Elite theory proposes that during periods of transition for nations, general elite consensus on key points of nation-building herald stability and institutionalization. Elite fracture and division portend further instability.

For democracy to take root after transition, elite consensus on democracy is necessary because the general mass can become indifferent or even hostile to democracies from time to time.

Political history of the last two centuries show us that introduction of democracy without backing of an elite settlement, almost surely leads to democratic backsliding sooner than later.

And this elite consensus on democracy and national interest needs to be robust because democratic politics by themselves tend to promote elite fracture. Democratic politics is divisive.

Bangladesh needs a robust elite consensus on democracy and economic growth. Are we reaching there? It seems not. It often seems that narrow political interests are triumphing over the post-Hasina unity we had for a little while.

Shafiqur Rahman is a Political Economist and Executive Director of Bangladesh Research Analysis & Information Network (BRAIN).

What's Your Reaction?