A Call From The Past

If our leaders want to know where this road leads, they do not need to look far. Pakistan chose the path of appeasing extremists. The consequences have been catastrophic.

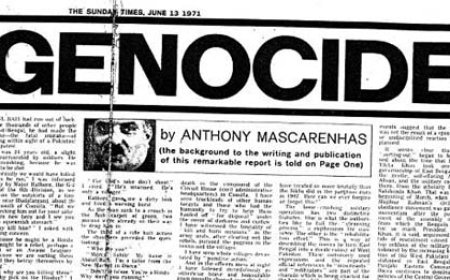

Before you read another sentence of this column, I beg you -- truly beg you -- to pause and read the 1953 Saogat editorial excerpt attached to this article.

Look carefully at those yellowed Bengali letters, written seventy-two years ago by editors who had lived through partition, communal bloodshed, and the terrifying rise of clerical power in Pakistan.

Read their trembling warning against the political weaponization of Islam. Feel what they felt as they watched Syed Abul A’la Maududi ignite a movement of sectarian hate, not in the name of faith but in the pursuit of power.

Those writers -- our intellectual ancestors -- were trying to tell us something vital: that a state cannot survive if it allows mobs or clerics to decide who belongs. A nation must be secular, not theocratic, if it hopes to keep its people safe.

Their warning was not abstract. It was rooted in the violence unfolding around them.

They saw how the anti-Ahmadi agitation of the early 1950s fractured West Pakistan, stirred mobs, paralyzed governance, and pushed the state toward authoritarianism.

They recognized that the real threat to Islam did not come from any sect, but from those who used Islam as a political cudgel. They begged Pakistan’s leaders not to surrender the state to those forces. If there is one thing you read today, read that screenshot. Because in 2025, Bangladesh stands at the edge of repeating the very same mistake.

What we witnessed recently at Suhrawardy Udyan was not a fringe skirmish or an isolated religious gathering. According to The Daily Star, thousands assembled under the banner of Khatme Nabuwat, joined by political leaders from the BNP, Jamaat-e-Islami, Islami Andolon Bangladesh, and clerics flown in from Pakistan, India, Nepal, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

Their demand was explicit: declare the Ahmadiyya Muslim community non-Muslim, confiscate their literature, and bar them from mosques. Their warning was equally explicit: if the government refuses, “tougher programs” will follow.

And what did the interim government led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus say in response? Nothing. Not a word of condemnation. Not a sentence of reassurance. Not a single reminder to the nation that the Constitution prohibits the state from determining who is or is not a Muslim.

This silence is not neutrality. It is abdication. From the first day of this interim administration, religious minorities have stood exposed. Threatened communities have heard nothing from the highest levels of government except diplomatic silence wrapped in the language of harmony.

But harmony is not maintained by silence; it is maintained by courage, by action, and by a government willing to protect its most vulnerable citizens. Yunus’s administration has offered none of that. Instead, it has allowed hatred to speak louder than law.

The violence did not begin in 2025, nor did the government’s failures. Bangladesh’s history of anti-Ahmadi persecution stretches across decades. The attack on the Ahmadiyya headquarters in 1992, the killing of an Ahmadi imam in 2003, the besieging of Ahmadi mosques in 2004, and the horrifying mob violence in Panchagarh in 2023 were not spontaneous bursts of rage.

They were the predictable result of years in which the state refused to enforce its own laws. When mobs attacked Ahmadi homes and torched shops during the 2023 Jalsa Salana preparations, The Daily Star’s law desk wrote that such violence was “the product of failures of the state for a long time.” That remains true today.

The law is unambiguous. Incitement to violence is illegal under Section 505 of the Penal Code. Article 12 enshrines secularism. Article 41 protects freedom of religion. And yet governments -- past and present -- have preferred appeasement over enforcement. The Yunus administration is simply the latest, and perhaps the most disappointing, because it arrived in a moment of hope.

If our leaders want to know where this road leads, they do not need to look far. Pakistan chose the path of appeasing extremists. The consequences have been catastrophic. As documented by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, Pakistan’s 1974 constitutional amendment declared Ahmadis non-Muslim, and its 1984 ordinance made it a crime for an Ahmadi to identify as Muslim, recite the kalima, say Assalamu alaikum, or call their house of worship a mosque.

These laws enabled a system where Ahmadi graves are desecrated, their mosques demolished, their voting rights stripped, their identity criminalized, and their lives devalued. Amnesty International’s 2025 report confirms the pattern continues today: forced affidavits banning Ahmadis from Eid rituals, preventive detention, police orders restricting prayer, and routine mob killings.

What is striking is how Pakistan’s descent began -- with a rally not unlike the one at Suhrawardy Udyan. The same slogans. The same threats. The same demand to declare Ahmadis non-Muslim. The Saogat editors saw the danger instantly. They wrote that such agitation would destroy peace, sow division, and push the state toward chaos. They warned that once a government starts bending to clerical demands, it ceases to govern at all. They wrote that persecuting any community in the name of Islam was not strength but civilizational weakness.

Bangladesh, born out of the rejection of Pakistan’s theocratic experiment, should not need these reminders. Our freedom struggle was not only about land; it was about the right to live under a secular constitution where citizenship is equal and inviolable.

And yet in 2025, under a government led by a Nobel laureate, the country cannot muster even a single forceful statement defending the rights of a threatened minority.

This is not the Bangladesh our martyrs imagined. It is not the Bangladesh our thinkers fought for. And it is not a Bangladesh that any of us should be willing to accept.

Our ancestors knew better. The Saogat editors were not writing from theory or ideology; they were writing from experience. They had watched a state destroy itself by empowering those who claimed to speak for God. They understood that the price of silence is paid in violence. They understood that persecuting a minority erodes the foundation of the entire nation. They understood that no society remains whole if it allows its most vulnerable to be sacrificed for political convenience.

So I ask you again: read the screenshot. Read it not as history, but as warning. Read it as a message addressed to us across seventy years. Read it as a plea from those who saw what happens when a state abandons secularism and allows cruelty to masquerade as piety. And read it knowing that the danger they described is unfolding again before our eyes -- this time in Bangladesh, and this time under a government that should have known better.

If we fail to listen now, we will have no excuse later. Our ancestors tried to spare us this fate. They left us their words as a map away from ruin. All we have to do is heed them.

Omar Shehab is a theoretical quantum computer scientist at the IBM T. J. Watson Research Center, New York. His work has been supported by several agencies including the Department of Defense, Department of Energy, and NASA in the United States. He also regularly invests in the area of AI, deep tech, hard tech, and national security. He is also an alumnus of the Shahjalal University of Science and Technology.

What's Your Reaction?